When I was a little kid, I used to think it was weird that we called black and white films “black and white.” See, they weren’t really black and white, I had reasoned, and it was actually fairly rare that anything within them would ever be totally black or totally white. Rather, they were a subtle rainbow of grays, so shouldn’t we call them “gray and gray” movies?

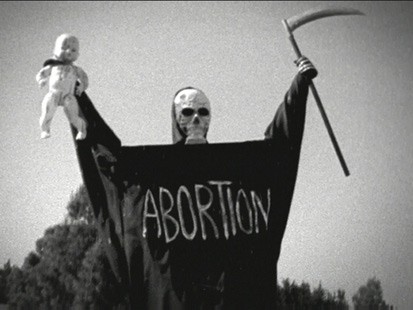

American History X director Tony Kaye’s incendiary abortion documentary Lake of Fire, the result of an epic 18-year creation process, is shot in 35 black and white, and the nature of the term has never been more appropriate. Whatever our views on abortion, too many of us tend to see the issue in black and white—certainly most of the people Kaye captures on film do—but in actuality, it’s anything but, a point Kaye drives home with nearly volcanic force by the end of this extraordinary work.

The length of time Kaye spent making it allows us to witness the issue, the activists and the shifting frontlines firsthand over the course of decades; he covers a March For Life event in 1992 at the dawn of the Clinton administration, and also the recent South Dakota statute that returned the state’s laws to a pre-Roe v. Wade status. He’s not just summing up the recent history of the abortion conflict in America, he’s seemingly filming it live as it unfolds.